Much has been written about Georgiana’s life, often focusing on her relationships and role as an 18th-century ‘socialite’. However, her life was far richer and more rewarding than many may suppose – she was a writer of poetry and prose, a political agitator and amateur diplomat, a tastemaker, keen musician and traveller, mineralogist and a forward-thinking parent.

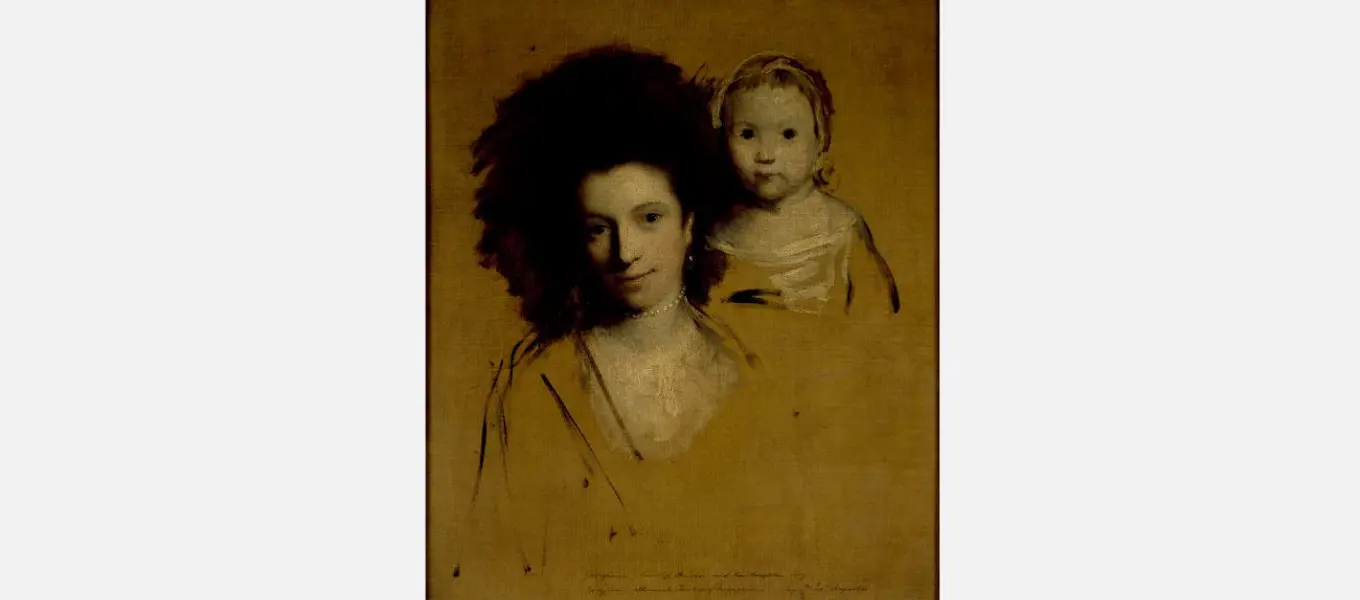

An unfinished portrait of Georgiana, Countess Spencer, and her daughter, Lady Georgiana Spencer

Sir Joshua Reynolds c. 1759

Born to the Spencer family at Althorp, Georgiana (pronounced ‘jaw jayna’) was the eldest of three children born to John, the future 1st Earl Spencer and his wife Margaret Georgiana.

Theirs was a happy household and Georgiana and her siblings were raised in expectation of making good marriages to partners from similar families and were equipped with the skills and accomplishments it was felt would enhance their prospects. The family were well-travelled and, whilst in Spa in the Netherlands, met William, 5th Duke of Devonshire (1748-1811).

Two years later in 1774, aged just 17, Georgiana married the Duke and became mistress of Chatsworth, Hardwick Hall, Chiswick House and Lismore Castle, as well as the estates at Londesborough and Bolton Abbey in Yorkshire.

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Richard Cosway. 1789 (read more)

She faced a huge responsibility, ensuring the houses were well run, overseeing their staffing and upkeep, and the well-being of the servants and of those living in the estate villages. Her mother-in-law would normally have given her what we might now call a “hand-over”, but the Duke’s mother, Lady Charlotte Boyle, had died 20 years earlier so Georgiana was left to manage largely alone.

…her youth, figure, flowing good nature, sense and lively modesty, and modest familiarity, make her a phenomenon.

English writer and politician, Horace Walpole (1717-1797), on Georgiana

Embarking on her marriage full of optimism, Georgiana was described as having a warm and vivacious personality, while her husband was regarded as being more reserved. The new Duchess enthusiastically established herself at the heart of London society, welcoming fellow aristocrats, royalty, actors, playwrights and musicians to her home. She also entertained prominent members of the Whig political party.

The Whig party advocated independence from the Crown but didn’t suggest that anyone outside the landed classes should have a bearing on politics. Unelected radicals— critical of both the Whig and opposing Tory parties — questioned how Parliament could be truly independent if controlled by aristocratic dynasties

The 1784 general election saw Georgiana take a surprisingly prominent role, campaigning in the streets and attending meetings. Unusually, this was not in support of a member of her own family, but instead, she was a figurehead for the entire party.

More usually, aristocratic women were expected to act as society hostesses and charitable patrons to support and further the political ambitions of their male relations. Women performed these roles within an accepted sphere as an extension of their usual social and domestic duties.

In order to undermine the power of the landed classes, the radicals particularly criticised aristocratic women campaigners in the press, satirical cartoons, public comment and articles.

Georgiana’s activities and those of her friends and relations were reported and ridiculed, partly because her behaviour and actions were viewed as transgressive.

Georgiana was particularly singled out, in one cartoon she was depicted as a man, tall and striding, carrying men to the polls to vote in favour of the Whigs. In another, the 5th Duke was depicted as a cuckolded husband, left at home literally holding the baby.

Cartoons by popular caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827) lampooned her as ‘the Butcher kissing Duchess’, accusing her of exchanging kisses for votes. Georgiana would write “… I am really so vexed (tho I don’t say so) at the abuse in the newspapers that I have no heart left. It is very hard they shd single me out when all the women of my side do as much…”.

'The Devonshire, or most approved method of securing votes', satirical cartoon by Thomas Rowlandson. 1784

After the election, Georgiana would continue to support the Whigs, although more privately and had an informal, though influential, role advising King George IV, particularly during his tenure as Prince Regent.

Georgiana was keenly aware of her public image and the impact it had on her self-image. Aged just 19, she wrote a poem titled “To Myself” which addressed the public’s perception of her. The poem, along with numerous letters and notebooks, is still preserved in the archives at Chatsworth.

In 1778, a novel entitled 'The Sylph' was anonymously published under the name ‘A Young Lady’, the novel is popularly attributed to Georgiana due to similarities with her own life. In around 1799, The Passage of the Mountain of Saint Gothard was privately printed. She kept a journal and was a keen correspondent, most famously penning letters written in her own blood to her eldest three children when in exile expecting her fourth child.

Georgiana’s signature

Gambling at cards was a central part of Georgian society with games played at clubs and at home, often late into the night. Georgiana had learned to play cards as a child and soon accrued large debts which would plague her for the rest of her life. It was only after her death that the full extent was realised and her husband and son made a public appeal to those who believed themselves owed from her estate to come forward.

A gaming table at Devonshire House. 1791. Thomas Rowlandson.

In 1782 Lady Elizabeth Foster (1759-1824) and Georgiana began a friendship which would last the rest of Georgiana’s life. Elizabeth, known as Bess, became a companion and support to the Duchess but Bess also had a relationship with Duke.

The three lived together - the relationship an open secret - with Bess travelling to the continent to give birth to two illegitimate children, Caroline St Jules (1785-1862) and Sir Augustus Clifford (1788-1877). Initially, the children were fostered out to other families but in later years they were admitted into the family and socialised with their half-siblings.

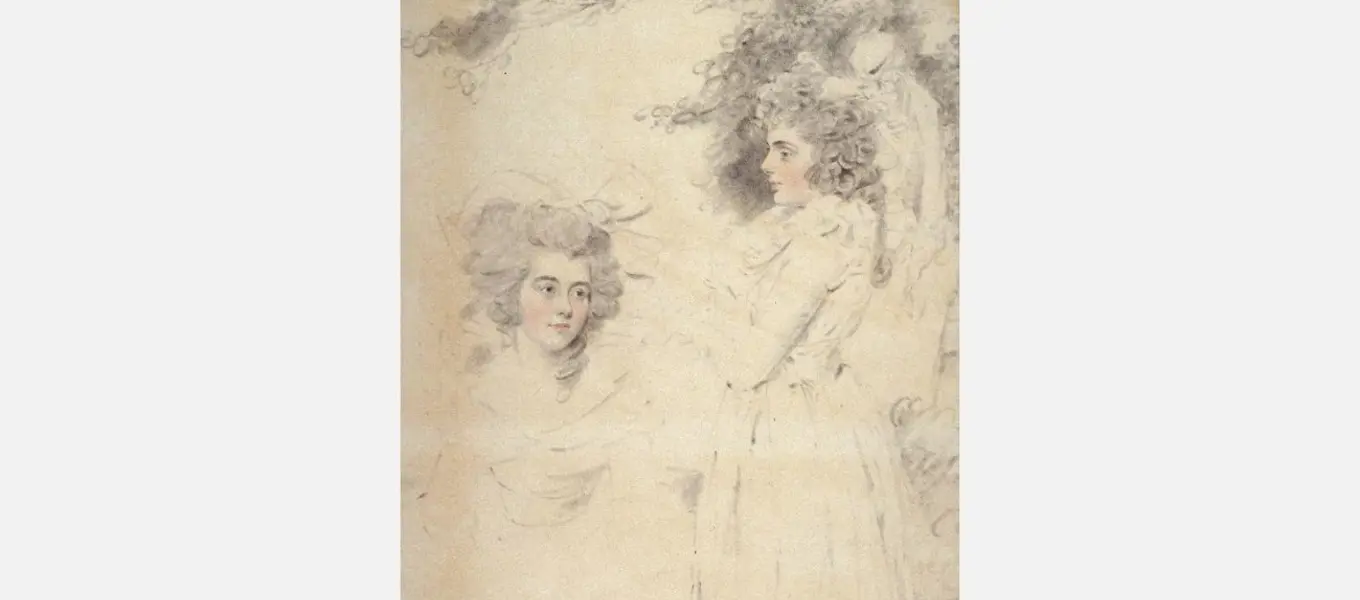

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire and Lady Elizabeth Foster. C. 1785. John Downman.

After nine years of marriage, the Devonshires would celebrate the birth of their first child, Georgiana (1783-1858) known as Little G, who was followed two years later by Harriet (1785-1862), known as Harryo. The sisters were joined by a brother William, known as Hart, who would become the 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858) in 1790.

Portrait of the Ladies Georgiana and Harriet Cavendish, daughters of the 5th Duke of Devonshire c. 1788. After Richard Cosway.

Georgiana was a follower of the child-rearing methods advocated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). The French writer proposed that children benefited from nurturing and affection and that care should be taken in their early years to ensure their development was enhanced by positive experiences.

To the dismay of her mother and the derision of many others, Georgiana insisted on nursing her babies herself and was far more involved in their everyday lives than was typical for a woman of her class. To her children, she was a loving and familiar presence and in later years they would recall her company and care with pleasure.

Sadly Georgiana was denied the opportunity to raise her fourth child, Eliza Courtney (1792-1859) because she had been conceived during an affair with politician Charles Grey (1764–1845). The Duke exiled Georgiana, forbidding her to return until invited and only on the condition that the baby was placed elsewhere. Georgiana was able to see Eliza as she grew up, acting as an unofficial god-parent, but Eliza was only told of her parentage after Georgiana’s death. Eliza named her first daughter Georgiana and her second Elizabeth Georgiana.

Unhappy child of indiscretion,

poor slumberer on a breast forlorn

pledge of reproof of past transgression

Dear tho' unfortunate to be born

Verse from a poem written by Georgiana to Eliza.

Lithographic plate from 'The Passage of the Mountain of Saint Gothard' drawn by Lady Elizabeth Foster

Georgiana was well-travelled, visiting France, Italy, Germany and Switzerland and wrote about her experiences of the woods, Alps and lakes, the discomforts of travel and the dangers of robbers and bandits. Her poem 'The Passage of the Mountain of Saint Gothard' was inspired by these events.

Travel also gave Georgiana the opportunity to expand a growing collection of minerals, of which she made an especially scientific study, earning her respect for her disciplined approach to their cataloguing and collection.

One spectacular specimen of quartz, standing over three feet high, was gifted to her after the opening of the Simplon Pass in Switzerland in 1793 and can be seen at Chatsworth today. The Duchess engaged mineralogist and antiquarian White Watson to catalogue her collection and to teach the rudiments of mineralogy to her three eldest children.

A selection of minerals belonging to Duchess Georgiana, preserved in the Devonshire Collection

Travel introduced her to people of interest, perhaps the most notable being Marie Antoinette with whom she began a friendship which lasted until the French Queen’s death in 1793. Friendship with the French Queen allowed Georgiana to become familiar with Royal and aristocratic society and customs as well as fashions in clothing and interiors. She brought Sèvres porcelain to Derby to be copied, purchased furniture from craftsmen favoured by the French court and popularised a simpler style of dressing.

After years of ill health and enduring blunt and brutal medical interventions which had impaired her sight and left her weakened, Georgiana’s final illness occurred in March 1806. She died at Devonshire House, the family’s townhouse in Piccadilly, aged just 48.

Mourning book for Georgiana, compiled by Lady Caroline Lamb. 1806.

Thousands of people congregated at Devonshire House in a public marking of respect and mourning.

Georgiana was buried at the family vault at All Saints Parish Church (now Derby Cathedral) in Derby.

Commemorated in prose by her daughter, Little G who wrote "Oh my beloved, my adored departed mother, are you indeed forever parted from me—Shall I see no more that angelic countenance or that blessed voice—You whom I loved with such tenderness, you who were the . . . best of mothers, Adieu—I wanted to strew violets over her dying bed as she strewed sweets over my life, but they would not let me".

"The best-natured and the best-bred woman in England is gone."

George, Prince of Wales.