Some artists become well known for returning to the same subject matter – over and over again.

Rembrandt made a lot of self-portraits – over one hundred have been identified (paintings, prints and drawings).

Leonardo da Vinci left a rich insight into the curious working of his mind through his notebooks, sketchbooks and annotated drawings. Rembrandt did not leave many letters or written notes, yet the numerous accounts of his own face have come to serve as his autobiography. We must exercise caution – it can become too easy to read sadness and personal tragedy into what we are trying to interpret visually.

Image above: Cartoon by BT Schwartz credit Benjamin Schwartz/The New Yorker Collection/The Cartoon Bank

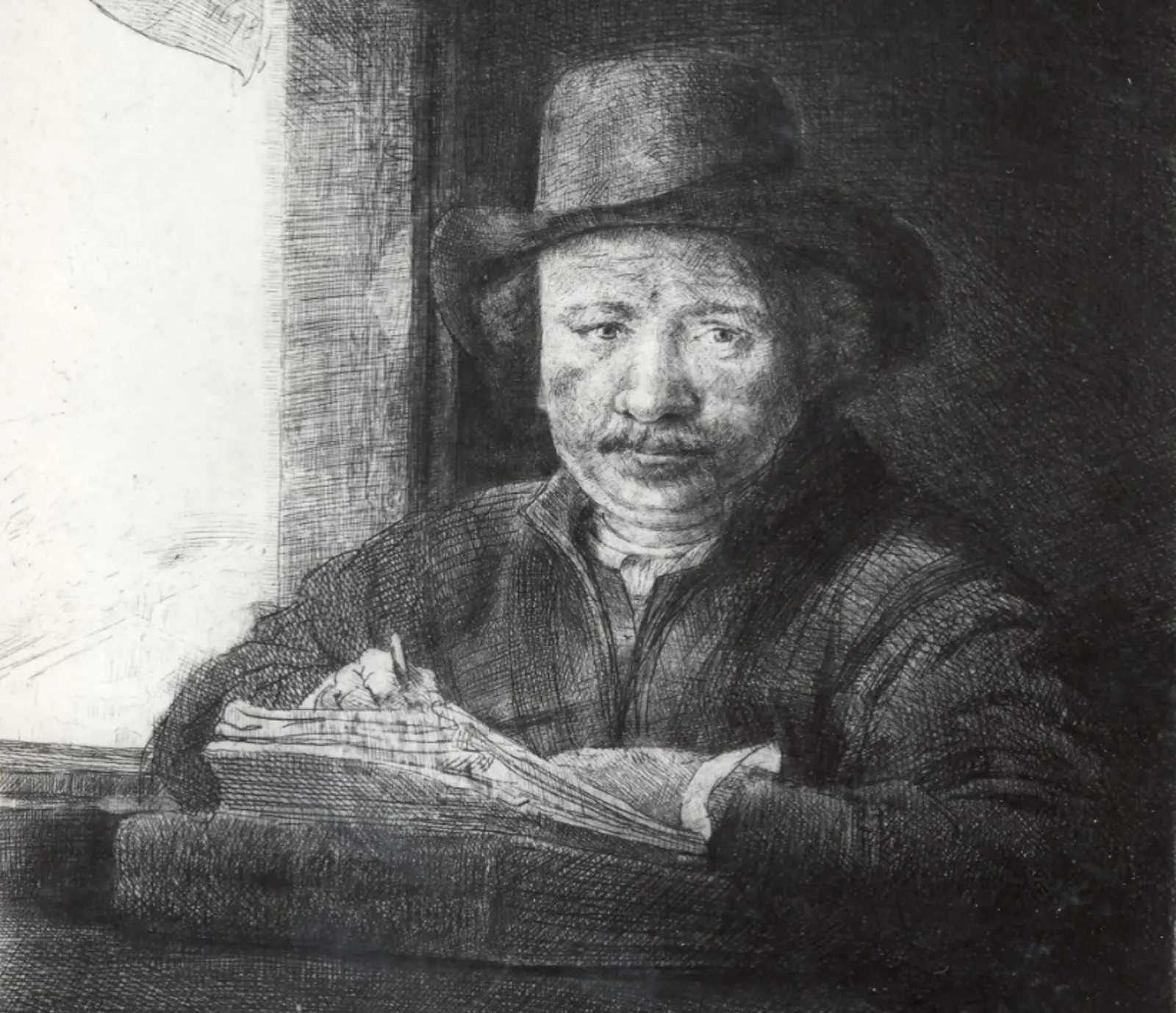

Use the zoom facility to take a closer look at this face.

Think of the words you might use to describe the expression on the man’s face.

Now look at the rest of his body and in particular his pose and body language.

With drawings (and paintings or photographs) of people, it is interesting to take some time to consider the following things:

- Facial expression

- Hands

- Pose / body language

- Props and accessories

Take a moment to do this now.

Historical drawings (and paintings) – like history itself – can often throw out new ideas or connections that completely transform our interpretation.

Take a look at some of the props and accessories and try to identify what kind of person we are looking at here.

The Rembrandt drawing you are looking at is almost 400 years old and was, for a long time, thought to represent St Augustine, an early Christian and bishop. This identification was based upon the visual evidence: a man, seated at a desk, contemplating a book. Behind him, his bishop’s garb hangs on a hook.

If you are new to looking at art or studying art history, beware the conclusions easily reached by piecing together visual clues. It is satisfying when objects and arrangements are pieced together to identify a subject or theme. It is also possible for new evidence to change everything.

Drawn in the 1630s, it wasn’t until 1979 that the man depicted here was identified as a popular actor – Willem Bartholsz Ruyter [1587-1639] – who lived and performed in Amsterdam during Rembrandt’s lifetime. After being part of a touring troupe of actors, he worked from the late 1630s in Amsterdam, where he owned an inn.

Image: Rembrandt, Willem Ruyter as an Inn-Keeper c.1638-39, pen and brown ink with brown wash. Credit Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands/Bridgeman Images.

Rembrandt appears to have drawn Ruyter more than once. In the drawing above, also by Rembrandt, in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, he is cast, appropriately, as an innkeeper.

Compare the innkeeper Ruyter with our drawing of Ruyter as a bishop.

Artists often made preparatory sketches for finished paintings. Drawings can reveal different stages in the realisation of a finished artwork. Rembrandt made preparatory sketches for paintings, but of the large number of surviving drawings by him (around 1400) not many are linked to surviving or completed paintings and this drawing is no exception. We may never know why he made this drawing.

There is a critical difference between Rembrandt’s paintings and prints and his drawings: his paintings and prints were for sale – they were essentially his merchandise – whereas his drawings generally were not for sale and would not have been so publicly visible.

When looking across a selection of his surviving drawings (you can do this in your own time by searching resources online or in a library) you will get a real sense of his depth and range as an artist. No subject was too trivial for him; he drew from the streets around him, people from all walks of life, landscapes, animals.

Here are some other examples of Rembrandt drawings from the Devonshire Collections. Zoom in to enjoy the level of detail Rembrandt revelled in capturing:

Images: Rembrandt van Rijn drawings: Bend in the Amstel near Kostverloren House; View of Sloten; A thatched cottage by a large tree, a figure seated outside

Think again, for a moment, about what Rembrandt is remembered for today. He drew, etched and painted his own face repeatedly. He laid his own features bare for the world. Consequently, many people feel they know him, can read his feelings into the likenesses that are separated from us by the passage of four centuries.

Image: Rembrandt van Rijn, Self Portrait drawing at a window

Now return to the actor in his dressing room.

As well as his reputation for being a highly skilled draughtsman, Rembrandt is often also described as possessing the ability to communicate his subject’s humanity, the inner workings of the mind.

His sitter here is an actor playing a part. He is seen in the process of becoming his character. Identity and humanity are complex concepts in the 21st century. Psychology as we understand it today did not exist when Rembrandt was alive. Nevertheless, a penned portrait of another person getting ‘into character’ is a complex web of relationships captured here with amazing quickness.

Rembrandt the draughtsman

Let’s finish by thinking about how Rembrandt has created this drawing (he used pen and ink but try to think about how he used them).

Here, Rembrandt is working at speed. The face is rendered with short sharp lines (look at those pointed features). Some cursory hatching indicates shadow under the hat, across the man’s brow and down his nose. A very small number of lines conjure the key features of this face. Nevertheless it is a face with character. The strength of the line accentuating the tilt in the cap emphasises the downward pointing face. The eyes, mere loops of ink, look up with intent- focusing upon something wholly unconnected to us, the viewer. Is he immersing himself in the role he is playing or about to play? In this way, Rembrandt does not so much suggest an individual’s personality or humanity but certainly does get close to a person with a purpose.

The body is also suggested in a cursory way but here, there is much more visual information. It can take a few moments to realise that a riot of numerous lines suggest the fur lining, the volume of sleeves and the flex of limbs underneath.

Rembrandt’s handling of pen and ink are electrifying. The assured parallel hatching of the actor’s right hand and across the fabric covering his right shin almost resemble the vital life signs of a cardiogram. The possibility of movement at any moment is rife. With the physical energy of flicking his wrist, Rembrandt has animated this flat surface.

If Rembrandt felt there were errors in the placement of a line, we would never know.

A-level specification

Rembrandt is a specified artist in the Identity Topic.