Raphael arrived in Florence aged 21, fresh from his hometown of Urbino. For the rest of his life he worked mainly between Florence and Rome. It is likely this page of drawings dates to the early years Raphael spent in Florence.

Take a moment to consider this drawing. Note the number of isolated figures and the central group of the woman with two children.

Raphael has made good use of the paper surface here! The page has been filled with figures.

Separate elements of this page have been connected to different paintings by Raphael. Looking at these today, almost five hundred years on, they can show us how the immediacy of drawing enabled an artist to test and develop ideas, some of which might take years to appear fully fledged in paint.

Let’s start top right.

Image right: Raphael, Madonna della sedia, oil on panel. Credit Palazzo Pitti, Florence, ItalyPhoto © Raffaello Bencini/Bridgeman Images

This chubby little boy, wrapped in an adult’s arms, bears a resemblance to the infant clasped by his mother in Raphael's painting Madonna della sedia painted around eight years later. The position of arms and hands and the age of the child have changed, yet the central idea of the loving embrace might well have originated in this sketch. So, in this small sketch we might be seeing the seeds of an idea that took a number of years to make it into a final painting. This is worth remembering; ideas and poses stick around in Raphael’s visual memory.

Take a moment to spot the differences.

Note the cursory mark-making suggesting different parts of the child’s anatomy. The left foot is simply composed of two small loops of ink, the right foot with the briefest of curved outline. Many artists are skilled in conjuring a person or object with the bare minimum of detail – few are capable of doing so with the precision Raphael can demonstrate.

Now take a look at the infant standing to the bottom right.

Does this pose remind you of anything? Have you seen it before?

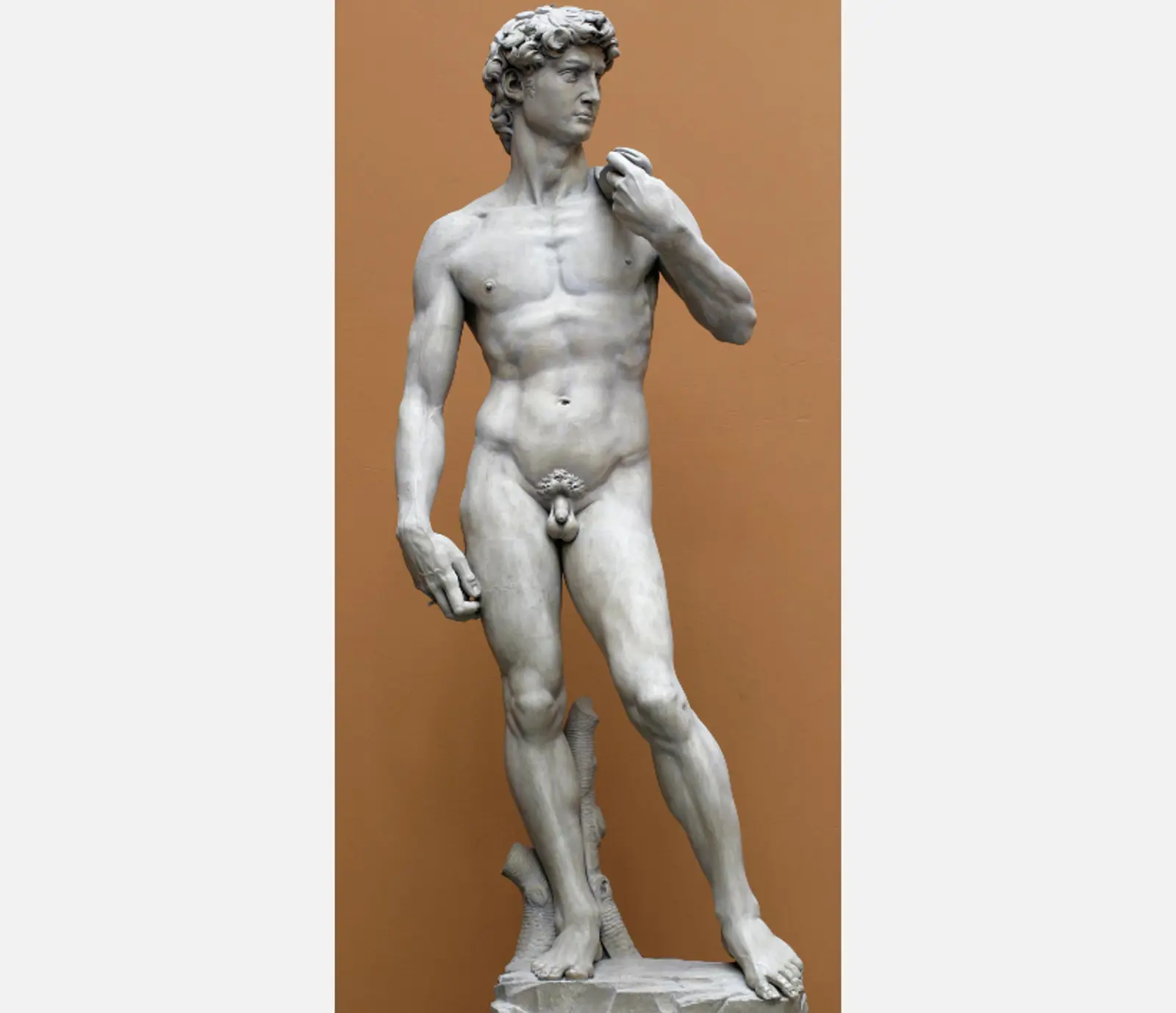

Image right:The East Cast Court at the V&A Museum with a cast of Michelangelo's David; Michelangelo Buonarroti sculptor, Clemente Papi cast-maker. Credit Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

There are obvious similarities when comparing the pose to Michelangelo’s David – which might at first be masked by the very different physique!

You might not agree, and that is fine, but it’s likely that Raphael was familiar with Michelangelo’s David. The original marble statue is in the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence. In 1504, it was installed in the Piazza della Signoria outside the town hall, where it remained until 1873.

Some scholars have disagreed that there is any connection between this drawing and David. There are more differences than similarities, perhaps, however the positioning of the arms do suggest a resemblance.

Compare Raphael’s drawing with Michelangelo’s sculpture. You will notice differences in the placement of the legs, the reversal of gesture, positioning of the head and also the weight distribution.

When Raphael refers to, or takes inspiration from, the work of another artist, it is rarely a case of straightforward imitation. He probes and adapts a pose or arrangement and seems to store it/them in his visual memory for a later date, which might be what has happened here. The painting below right was made a number of years after this drawing.

Image right: Raphael, Madonna in the Meadow, oil on panel. Credit Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria/Bridgeman Images

During his early years in Florence, Raphael drew mainly using pen and ink, developing speed and skill in doing so. The Madonna and Child was a subject he concentrated upon during this period.

This grouping of adult and children provide an insight into Raphael’s growing talent as a draughtsman. It might also reveal something of the influence that Florence had upon the young artist.

Raphael’s time in Florence corresponds with its reputation as one of the great artistic centres of Italy. The city’s artists were known for disegno (from the Italian for drawing or design). When applied to interpretations of art, disegno often refers not just to the ability to draw, but also to the invention or intellectual creation of the design.

Take a moment to consider the ways in which this drawing and painting support the idea that Raphael had technical skills and intellect and imagination.

Raphael’s technical skill in handling pen and ink combine with his capacity for design to communicate his ideas.

A sheet of drawings such as this one remind us that Raphael – whose paintings are often held up as examples of perfection, the peak of the High Renaissance – was learning all the time. He looked to other artists for ideas, explored figure poses and arrangements and sought solutions through the act of drawing. He wasn’t born amazing at this; he became amazing through practice.

It is almost as if we can see his thoughts on paper which often, many years later, were turned into decisive action in paint.

A level specification

Raphael is a named artists on the Art in Renaissance Italy 1420-1520 topic.