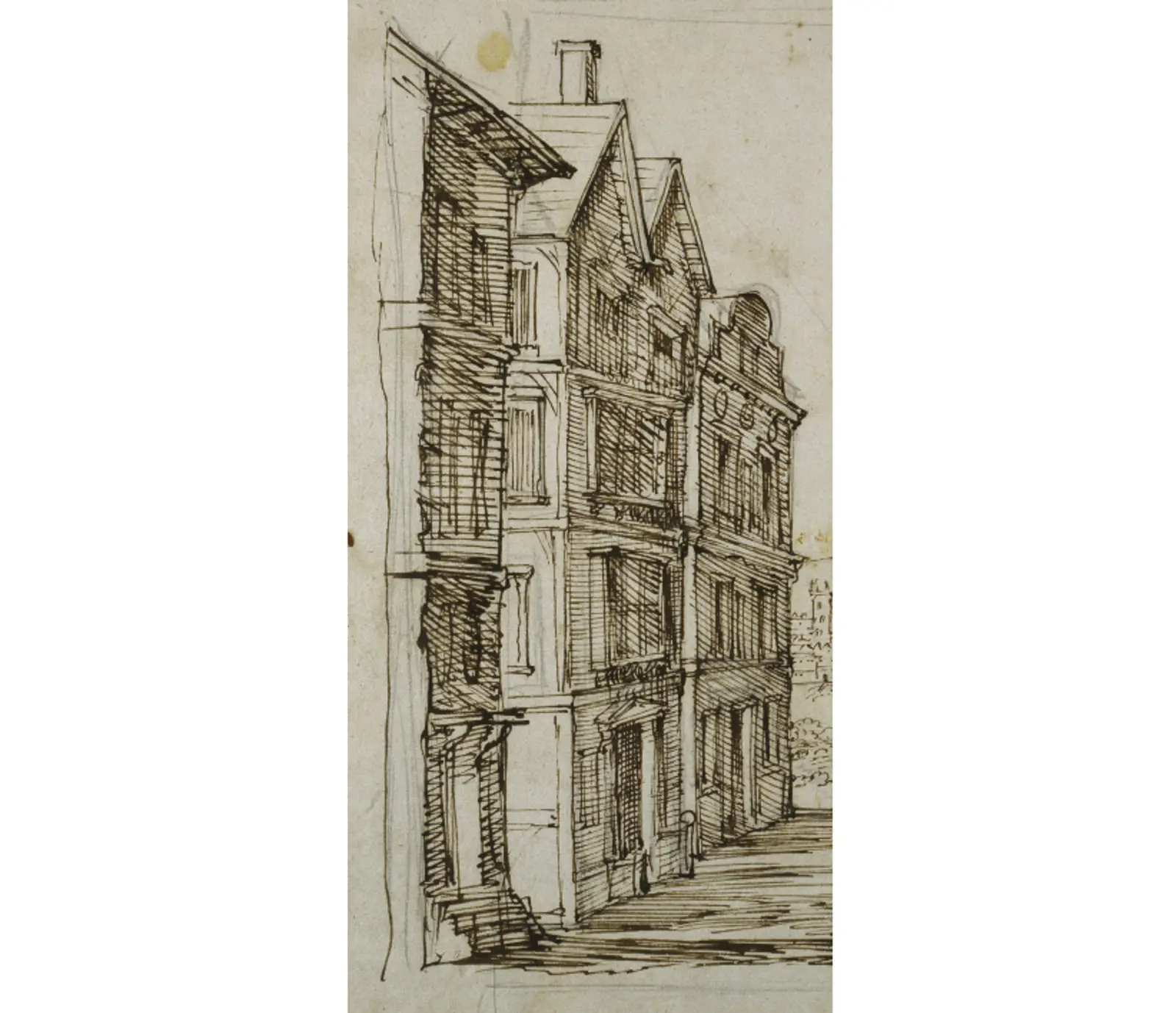

Compare a detail from this drawing with details of works by other artists.

Images from left: Inigo Jones; Rembrandt van Rijn, The actor Willem Ruyter in his dressing room, pen and brown ink on paper; Nicolas Poussin, The Sabine Women, pen and brown ink with brown wash

The lack of people suggests that human activity may not have been the primary concern of Inigo Jones when he drew this. This is interesting because artists often include a figure to give a viewer a sense of scale.

Inigo Jones was London-born and started his working life as a joiner/carpenter. At some point before he was 30, a rich supporter sent him to Italy to study drawing. He became well known as a costume and theatre set-designer. However, it is his architectural achievements that he is best remembered for today. Among other celebrated buildings, he designed the Queen’s House at Greenwich (his earliest surviving work) and the Banqueting House on Whitehall, London. The Queen’s House (for Charles I’s Queen, Henrietta-Maria) was the first purely classical building to be completed in England, and shows us how he absorbed ideas from architectural sources including ancient Rome and the 16th century Italian architect, Andrea Palladio.

Take a look at this detail of Jones’ London and the Thames Afar Off.

Are there any clues that this was drawn by someone who had a keen interest in the built environment?

Let’s zoom in just a little bit to think about the location. Right in the middle of the background we can see St Paul’s Cathedral. If you are familiar with this famous London landmark, you might not have recognised it here - the iconic dome is missing.

Inigo Jones lived through a century of great political turmoil and a number of history-defining events in his city of birth. In his lifetime (1573-1652), civil war broke out in England, the King was put on trial and executed (outside the Banqueting House on Whitehall, designed by Jones), and England became a republic (Jones died before the monarchy was restored).

The St Paul’s we see in this drawing is Old St Pauls, destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Zoom in a little more and we can see that Jones has captured a view from the south of the river Thames across to Old St Paul’s. The Thames runs through the background with four small vessels visible on its surface.

Same city, similar view, different artistic choices.

Comparing these two views of London before the great fire of 1666 is revealing. The main difference is that one is painted and one is drawn, so let’s put the artist’s materials to one side for now and concentrate on the choices they have made as picture-makers.

The unknown English artist shows the Thames as a busy thoroughfare congested with large and small vessels. The street scenes on the south side of the Thames (bottom right) show many people going about their daily business. Meanwhile on the north side of the river, in the immediate vicinity of Old St Pauls and further afield, every street, lane and alleyway is packed to the rafters with buildings big and small. Although nowhere near as congested or populated as it is today, we see London as a large and bustling metropolis.

Jones has been a little more economical with the level of detail conjuring the streets around Old St Pauls. The south bank of the river Thames shows a number of dwellings immediately surrounded by what look like tended and ploughed fields but this may be for aesthetic and presentation reasons rather than topographical accuracy. Our view positions us in the middle of a deserted street with three-storey buildings framing our line of vision and directing it, tunnel-like, forwards and downwards towards Old St Pauls, right at the centre of the distant cityscape.

This use of perspective (where an artist plots three dimensional space or objects on a two dimensional surface) plants us firmly on that deserted street, whereas there is nowhere for us to stand in the panoramic view painting of London.

The architecture on the left and right of Jones’ drawing give the composition symmetry. Diagonal, linear details of the facades recede in space, counter-balanced by horizontal lines indicating the end of the road, stretch of river and rooftop of the cathedral.

The symmetry and use of perspective make this drawing look more artificial; more heavily designed than the view painting.

That stage-like artifice is appropriate because this drawing is one of Jones’ designs for a masque – a theatrical piece of courtly entertainment involving dancing and acting wearing masks. Jones collaborated with poet and playwright William Davenant; the drawing is a design for the opening scene of Britannia Triumphans, performed at court in January 1638 and with the masquers led by Charles I. With its evident strong political overtones, it chimed with the Stuart King’s belief in his divine right to rule Great Britain. The stage setting, with all perspectival routes landing on Old St Pauls, symbolically reinforces the idea that London is more than a city and more than a scenic backdrop. It represents the whole of the kingdom.

While stage-like, this drawing calls our attention to another feature of Jones’ work that sets him apart from his contemporaries. He was the first English designer to use architectural perspective in his stage settings. So, while it might look staged to us today, it was intended to create the illusion of reality.

We have seen that Jones made choices about what to include in his view of London and how to set the scene, using devices he saw on his travels to Europe. We have also discovered that he has put these choices into the service of a higher purpose, supporting the allegorical intention of the theatrical production (a light-hearted court diversion on the one hand; a political tour de force on the other).

In some ways, the drawing reminds us just how complex identity can be. The drawing reveals layers of national, political, regal, courtly, public, private and personal identity.

Thinking, finally, about the personal identity of the artist, let’s return to the detail of the bottom left hand corner.

Image right: Rembrandt van Rijn, The actor Willem Ruyter in his dressing room, pen and brown ink on paper

There is such energy in the decisive straight and squiggly lines, the diagonal, vertical and horizontal parallel hatching and confidence in the pen loop creating the ellipses (above the doorway) on the nearest façade. Jones injects as much energy into an inanimate structure, breathing life into it through the sheer vitality of his mark making as Rembrandt does with his riot of thick, thin, jagged and serrated lines in his drawing The actor Willem Ruyter in his dressing room.

Something to think about

Portraits of artists are often referred to in an attempt to establish more about their identity and motivation. It was, and still is, common for artists to make portraits of one another and to make self-portraits.

Images from left: Anthony Van Dyck, Portrait of Inigo Jones; Inigo Jones, Self-Portrait

Compare the portraits above. The one on the left was made by Van Dyck, a Flemish artist who spent much of his artistic life in London as court painter to Charles I. His portrait of Jones is loosely based on Titian’s portrait of the architect and painter Giulio Romano. Presumably Van Dyck compares himself to Titian (a celebrated artist from the sixteenth century) and Jones to Giulio Romano (an influential architect and artist). Jones takes up the entire pictorial space as he looks off into the distance, hand on hip, in an idealised pose.

The one on the right is thought to be a self-portrait of Jones. He meets our gaze with a sideways glance, his lips pursed and his brow furrowed. The overall effect is quite different and leaves us with an entirely different impression of the artist.

This is the evidence left to us by the passage of history. A portrait or an empty stage set will only ever present a fragment of what has passed. We need to exercise caution in their interpretation. However, looking closely at the choices made by an artist, what line, tone or value they use to capture the subject, as well as the skilled manipulation of materials and techniques they use to do so, can be helpful in throwing light on the image, its purpose and meaning.

A-level specification

Jones is a specified architect in the Identities topic. English Houses with London and the Thames Afar Off demonstrates his interest in architecture, and the architectural elements of London old and new.