Yesterday saw the final episode of the TV adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel, Vanity Fair. Victorian readers of the book would have followed the development of the plot in a similar way to today’s television audience: the novel was serialised in the monthly magazine Punch during January 1847-July 1848, and readers would be made to wait impatiently for each new instalment. One of those readers was William Spencer Cavendish, the 6th Duke of Devonshire. The Duke loved contemporary literature, and met and corresponded with several well-known writers of his day, including Charles Dickens, Leigh Hunt, Elizabeth Gaskell, and Thackeray – whom he first met at Lake Geneva in summer 1839.

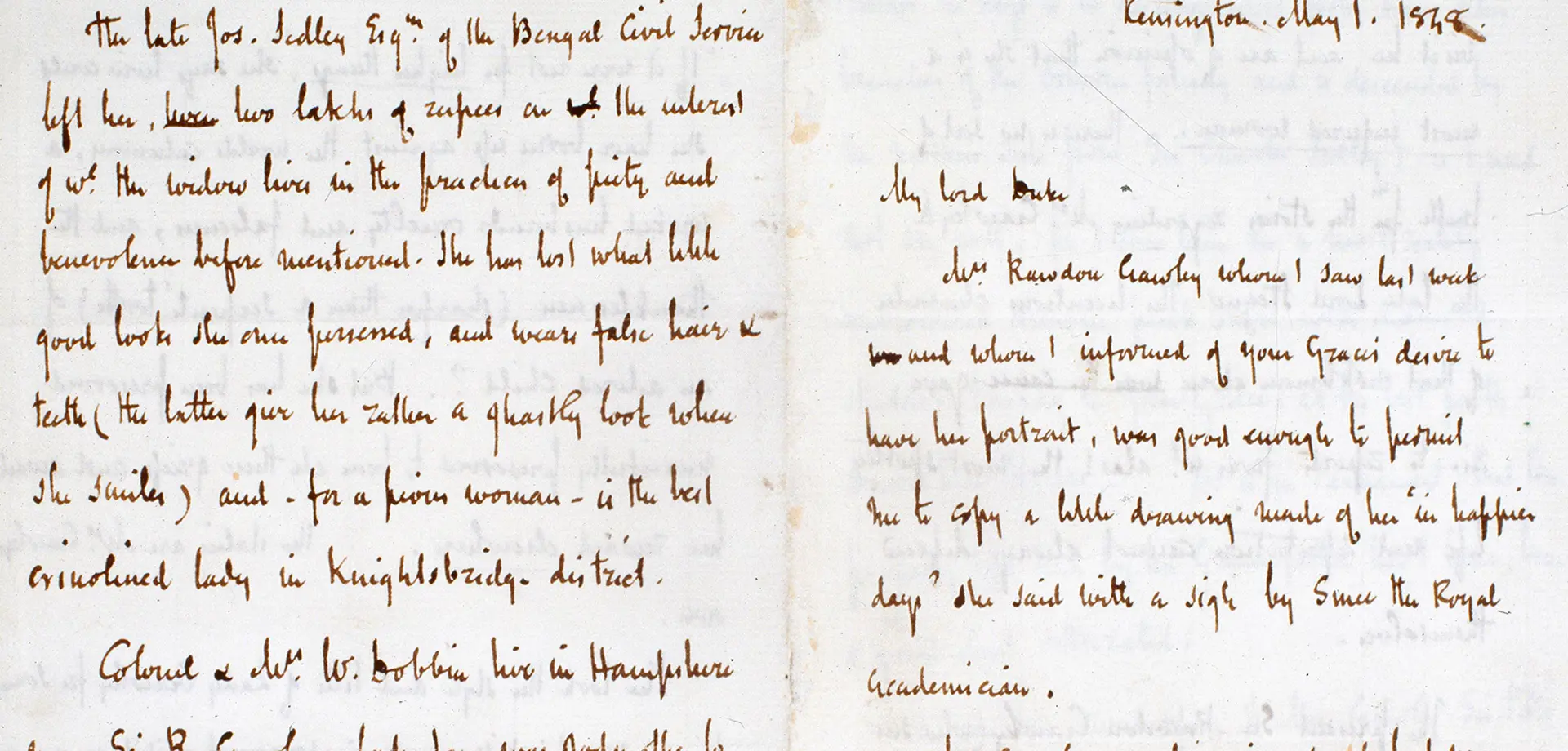

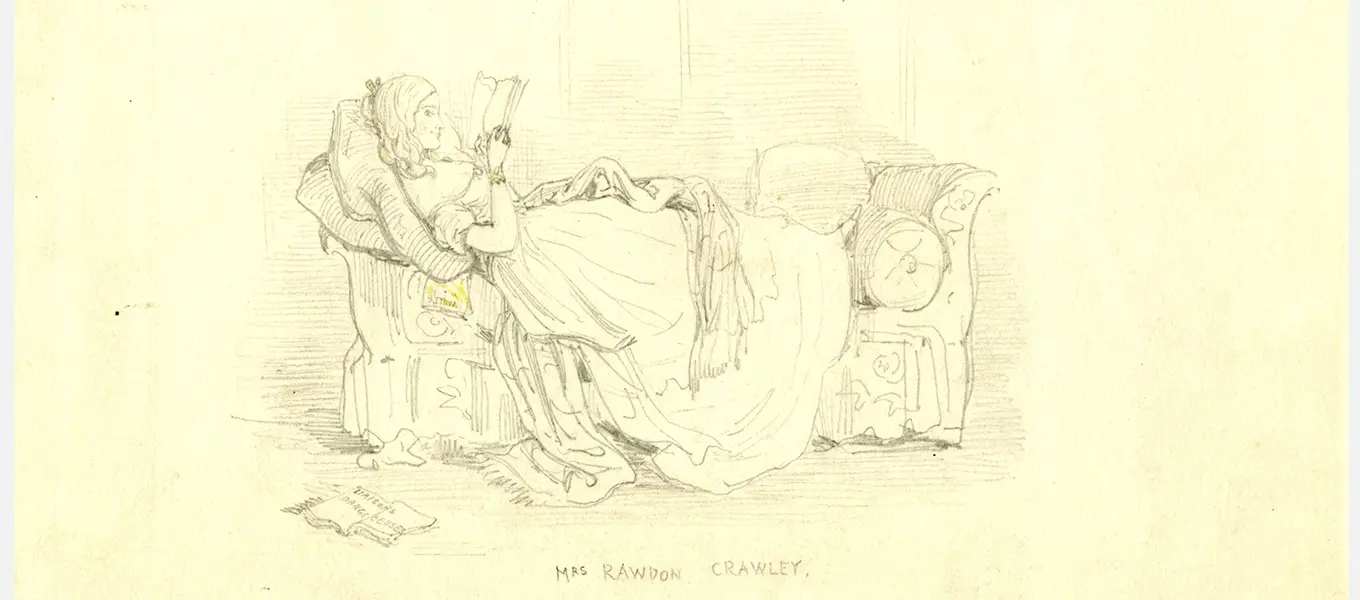

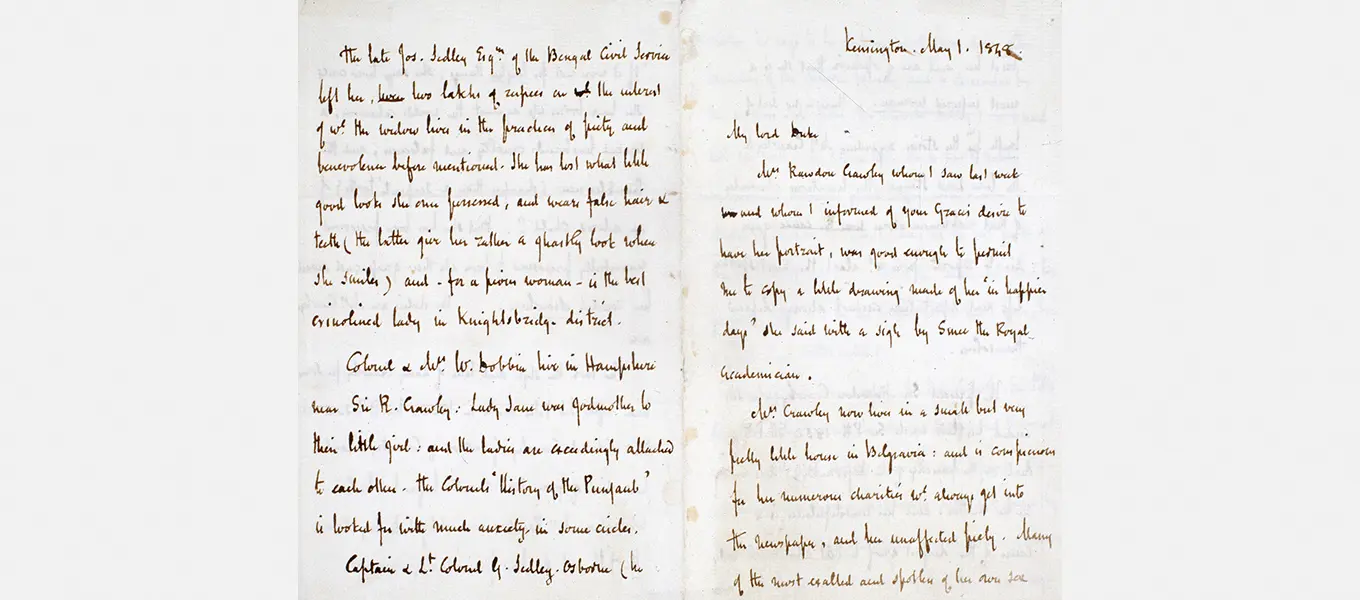

The Duke was clearly following the progress of Vanity Fair in Punch magazine, and before the novel had finished its serialisation he wrote to Thackeray asking for a portrait of the novel’s protagonist, Becky Sharp (or Mrs Rawdon Crawley). Thackeray was a skilled artist and illustrated many of his own books. He was only too happy to oblige the Duke, and duly sent a pencil sketch of Becky, reproduced below. In his accompanying letter, dated 1 May 1848, he pretends that it is taken from a sketch by the artist Sir Martin Archer Smee, showing Becky ‘in happier times’.

Thackeray’s letter is written in a delightfully gossipy tone. In it he updates the Duke on developments in Becky’s story and outlines her current situation in life – essentially giving his correspondent a sneak preview of how the novel did actually conclude; the account differs only in minor respects from what followed in the final two instalments as published.

Thackeray describes in typically satirical vein how Becky now ‘lives in a small but very pretty little house in Belgravia; and is conspicuous for her numerous charities which always get into the newspapers, and her unaffected piety.’ He stresses that ‘there is no sort of truth in the stories regarding Mrs. Crawley & the late Lord Steyne’. Her neglected son no longer sees Becky, a fact which causes ‘the greatest grief to that admirable lady’. We hear that Amelia and Captain Dobbin are happily married and living in Hampshire, while Becky lives alone: ‘she has lost what little good looks she once possessed, & wears false hair and teeth (the latter give her a rather ghastly look when she smiles)’ but she is still ‘the best crinolined lady in the Knightsbridge district’.

Thackeray also brings the Duke into his story, reporting that Amelia’s son was seen ‘in a most richly embroidered cambric pink silk shirt with diamond studs bowing to your Grace, at the last party at Devonshire House’ (the Duke’s London residence). The 6th Duke had a great sense of humour and would have greatly enjoyed this letter. A few months later, he invited Thackeray to Chatsworth, taking great delight in showing the writer around his house as an honoured guest.

The library at Chatsworth does not contain any of the Punch magazine issues in which Vanity Fair was serialised; publications like this tended to be seen as ephemeral and were often disposed of once read. However, there is a copy of the first book publication of Vanity Fair: typically, when the serialisation of a novel had finished, the book in its entirety would be published in volume form, and it is these editions that tend to be preserved in libraries today. The Chatsworth copy has the 6th Duke’s crest on the spine, so we can be fairly certain that he purchased the novel for his book collection – or perhaps he received it as a gift from its grateful author.