While on a work placement at Chatsworth, I was given the opportunity to look through the vast archives, including the letters of correspondence and private poetry written by Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire.

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire by Thomas Gainsborough.

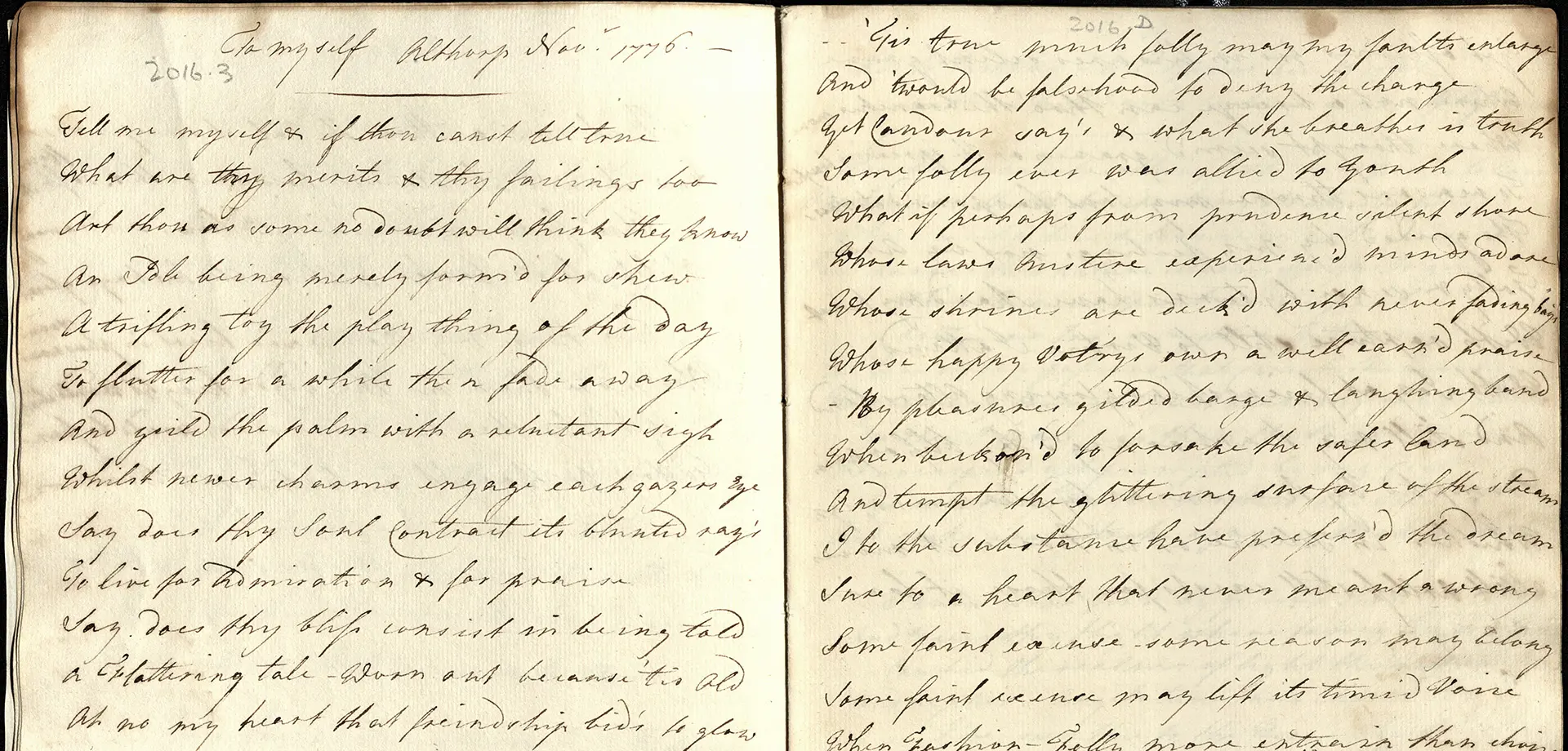

Whilst looking at various items, I came across a poem by Georgiana called ‘To Myself’. When I first read it, I almost couldn’t believe my eyes. It was like hearing Georgiana herself through the page, speaking directly about what it was like to be her, to be so famous at such a young age, and for everyone to think they know you, to judge you or categorise you without ever meeting you. It is an incredibly personal and intimate poem and shows a side of her that I hadn’t seen before.

Although Georgiana’s life has been widely documented in biographies and biopics, it can still be difficult to truly know her. As much as we delve into what we know of her private life and its various scandals, it is still challenging to grasp what she thought of it all and how she saw herself in relation to her fame.

The poem also struck me as significant because of its literary merit. As a student of manuscript verse, I jumped at the opportunity to analyse ‘To Myself’ and its intricacies. Even though the Duchess has had some works published which many critics assume to be hers, including two novels and a poem, these debates are often clouded by questions of authorship as she never published anything under her own name. In cases where critics assert they are her own work it is usually on the grounds their biographical similarities to her life, meaning little attention is given to their literary strengths.

However, I think that ‘To Myself’ could change that. What truly struck me was its distinctly mature expression of voice and imagery, and the way it sets out two distinctly different parts of Georgiana’s personality which exist within her simultaneously: the public and the private selves. It shows a side of Georgiana that cannot be accessed through biographical depictions, namely her inner monologue.

Georgiana was only nineteen years old when she wrote ‘To Myself’, which, when you read the poem, is particularly striking. She asks herself questions about her identity then answers back to herself in an attempt to come to terms with her public perception and how it relates to her private self. The first few lines are remarkable and set up public perception of her as an ‘Idle being merely form’d for show / A trifling toy the plaything of the day / To flutter for a while then fade away’. She expresses a perceptive analysis of throwaway celebrity culture before its true wake, and she comes across as self-aware and mature, perhaps more so than we have given her credit for.

She uses a rich array of imagery, setting up a dichotomy between flowing streams and sturdy trees to express her duality of self. The flowing streams represent vanity and the follies of her youth, which carries her away despite her best efforts to resist. At the end of the poem, she uses trees to juxtapose the rapid stream of vanity to establish a symbol of reason which equally resides within her. She paints a pastoral and intimate scene in the solitude of a private moment, where she joins with reason in a metaphorical exchange of vows.

I would strongly encourage anyone who wants to know more about Georgiana to read ‘To Myself’ and gain a much-needed glimpse into the inner life of a woman whose public life has been widely discussed. Perhaps we should pay more attention to her unpublished works and the potential they hold for insight about the nuances of Georgiana’s personality. This poem in particular, I think, allows us to see and embrace her downfalls and view her as a complicated and nuanced woman, just as she saw herself.