The 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858) was celebrated for welcoming tourists to Chatsworth House and its grounds. By 1850, weekday excursion trains brought large parties of day-trippers, while at weekends there were up to 2,000 independent visitors a day.

Amongst those visitors on Saturday 12 September 1857 were the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-1865) and her daughter Meta. Gaskell left an entertaining account of their visit in a letter to another daughter, Marianne. We know they travelled from their home in Manchester the day before, and on Saturday set out for Chatsworth as tourists, ‘to see the house with our green card’. At that time, the house and grounds were open to the public every day except Sundays, and admission was by a visitors’ ticket. Gaskell’s signature also appears in the 1857 visitors’ book for that day. They were shown around the house by a ‘nice looking housekeeper’. Our Historic Servants and Staff database suggests that this might have been either Mary Hastie or Phoebe Radley – the housekeeper and her deputy, who were also lifelong friends and shared the housekeeper’s wage between them.

Their tour was interrupted by the Duke’s valet, who invited them to lunch and dinner with the Duke and his other house guests, and informed them that a room was being made ready for them to stay overnight. Having only their travelling clothes with them, they were somewhat disconcerted by the prospect of having to dress for dinner with a Duke. On being shown to their rooms, Gaskell discovered that the curtains on her bed were of thick white satin stamped with silken rosebuds, and in the absence of suitable attire for a formal dinner, ‘Meta proposed that we should dress ourselves up in them’. The bed and its hangings still survive at Chatsworth.

Before lunch, the Duke himself appeared. He was wheeled in a bath chair, having been in poor health since suffering a stroke several years previously, but he showed the Gaskells some of his art collection which wasn’t on show to the public before leaving them in the care of Sir Joseph Paxton for lunch and afternoon activities. Gaskell commented that Paxton was ‘quite the master of the place’. The ladies in the party were taken in carriages out into the gardens, marvelling at the fountains and waterworks, and (‘like Cinderella’) being driven through Paxton’s Great Conservatory.

Following dinner, at which many more visitors were in attendance, they wandered through the Sculpture Gallery and Orangery, which were lit up for the occasion. They were treated to a programme of music from the Duke’s own private band, during which Gaskell sat next to the Duke. She commented that his hearing (which had always been poor) seemed to be better when music was played, and they talked throughout the concert.

We can only speculate on what they discussed, but the Duke had strong literary interests and only the previous month had made a visit to see Patrick Brontë in Haworth. Gaskell’s famous biography of her friend Charlotte Brontë had appeared earlier in 1857. It was received with much praise, but Gaskell also faced a barrage of complaints from people who felt they had been misrepresented in the book – and in two cases legal action was threatened. She had therefore spent a stressful summer revising it for a new, third, edition.

From the outset, her biography provoked fascination with the lives of Charlotte Brontë and her sisters, and in subsequent years more and more literary tourists made the journey to Haworth to see where they had lived and written their novels. It seems the Duke of Devonshire was amongst the earliest of these literary pilgrims – probably prompted by Gaskell’s book.

The morning after their dinner, Gaskell sat down in her room to write the letter in which she so vividly described her visit, using ‘a delicious pen’. She confessed that she had no idea where she was supposed to go for breakfast ‘in this wilderness of a palace of a house’.

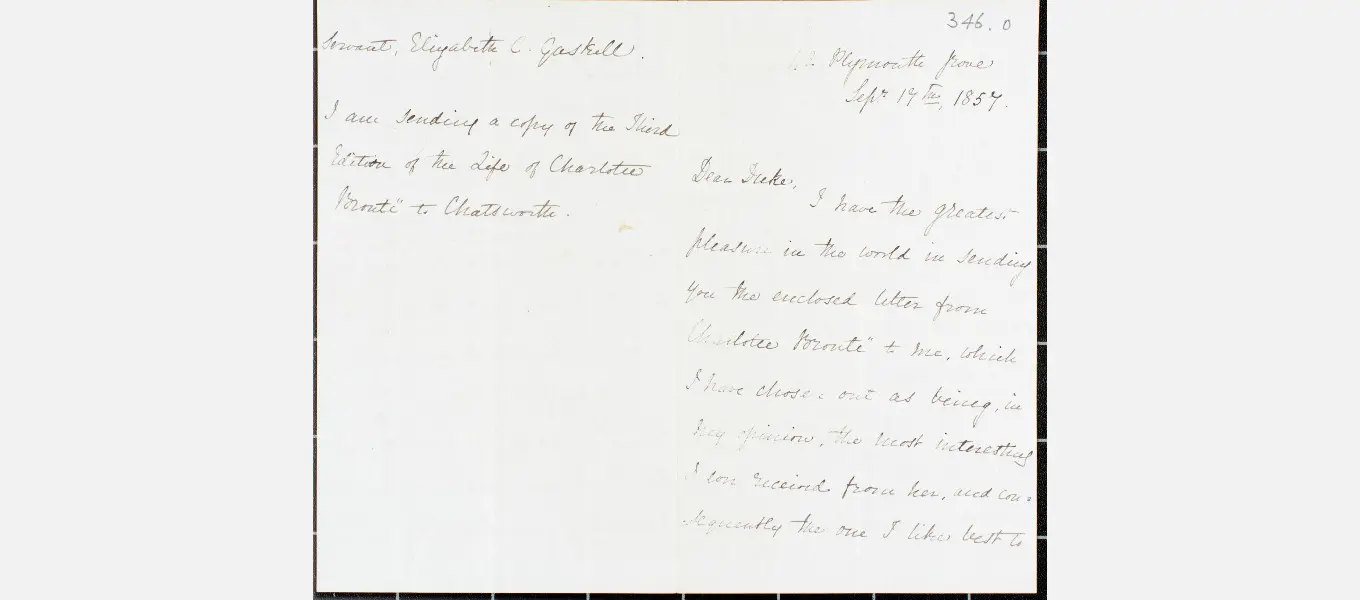

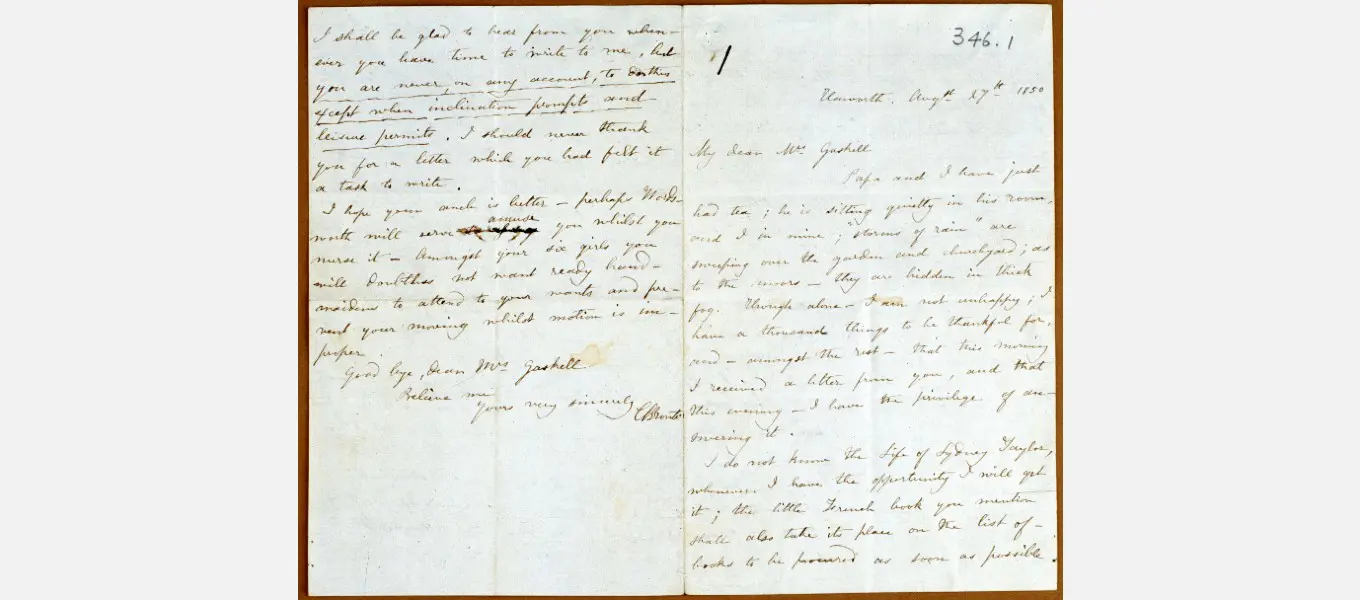

However, she and Meta successfully made their way home in the end, and Gaskell wrote a thank-you letter to the Duke for his hospitality; she also thanked him for his ‘sympathizing words’, suggesting she confided in him some of the troubles she had experienced over her biography of Charlotte Brontë. Enclosed with the letter was a precious gift for the Duke: ‘I have the greatest pleasure in the world in sending you the enclosed letter from Charlotte Brontë to me [which] I have chosen out as being, in my opinion, the most interesting I ever received from her, and consequently the one I like best to offer to your Grace.’

The 6th Duke has a wonderful archive: he carefully compiled scrapbooks about his activities and preserved his correspondence. The letters from Gaskell and Brontë were no doubt amongst his most treasured literary letters.