Many of us are currently buying presents and preparing for Christmas – but how was the festive season celebrated in the past? Here we examine how Christmas customs changed over a 300-year period by taking a look at Christmas in the 17th and the early 20th centuries, drawing on the Devonshire Collection Archives.

Christmas greetings

Today most of us send Christmas greetings in the form of printed cards, but until the mid-19th century people simply exchanged greetings by letter.

The earliest Christmas letter in the archives dates from 6 December 1605, and was sent by Henry Cavendish to his mother, Elizabeth, Dowager Countess of Shrewsbury, better known as Bess of Hardwick.

Images: 1. Christmas greetings from Henry Cavendish to his mother, Bess of Hardwick, 2. Bess of Hardwick, © The National Trust

Although he was her eldest son and heir, Bess referred to Henry as her ‘bad son’ and added a codicil to her will to disinherit him in 1603. In the letter above, written two years later, Henry sends Christmas greetings from himself and his wife:

‘Good maddam and my most honourable good Lady and mother, I and my wyfe are most bounden to your Honourable Ladyship and through your goodness and bownty, We ar lyke to keepe the meryar Chrystemas, Whearin never day shall passe, that we wyll not have a dutyfull remembrance to your Ladyship God send your Honor many a Healthfull and merry Chrystemas’. He signs himself ‘Your Ladyshyps humble and obedyent Soonne, Henry Cavendysshe’.

The polite and deferential language, and the low positioning of Henry’s signature on the page, may reflect a desire to reinstate himself in his mother’s opinion (and her will); if so, his attempts were unsuccessful.

Exchanging gifts with Elizabeth I

While there is an ancient tradition of exchanging gifts during the festive season, until the 19th century presents were generally given at New Year rather than on Christmas Day, and from medieval times it was customary for the monarch to be presented with gifts at New Year.

Bess of Hardwick tried to ensure the good favour of Queen Elizabeth I by presenting her with numerous lavish gifts over the years. The Queen’s gifts in return tended to be less costly. She often gave presents of gilt plate.

Above is an inventory of plate owned by Bess, written around 1599, which records several presents of ‘guilt boles’ (gilt bowls) that Bess received from the monarch as New Year’s gifts during the 1590s.

Aside from the extra effort she made to find something suitable for the Queen, Bess’s general preference was to give money gifts. This list of the sums she gave out at Hardwick Hall for New Year 1601 is written in her own hand.

It includes family as well as staff. At the top of the list are her granddaughter Arbella Stuart, and ‘bad son’ Henry (or Harry) – both of them later disinherited but still in favour at this time.

Dinner is served

Some documents in the archives provide a glimpse of what was eaten at Christmas in the 17th century. Many of these foods remained popular right through to the 19th century.

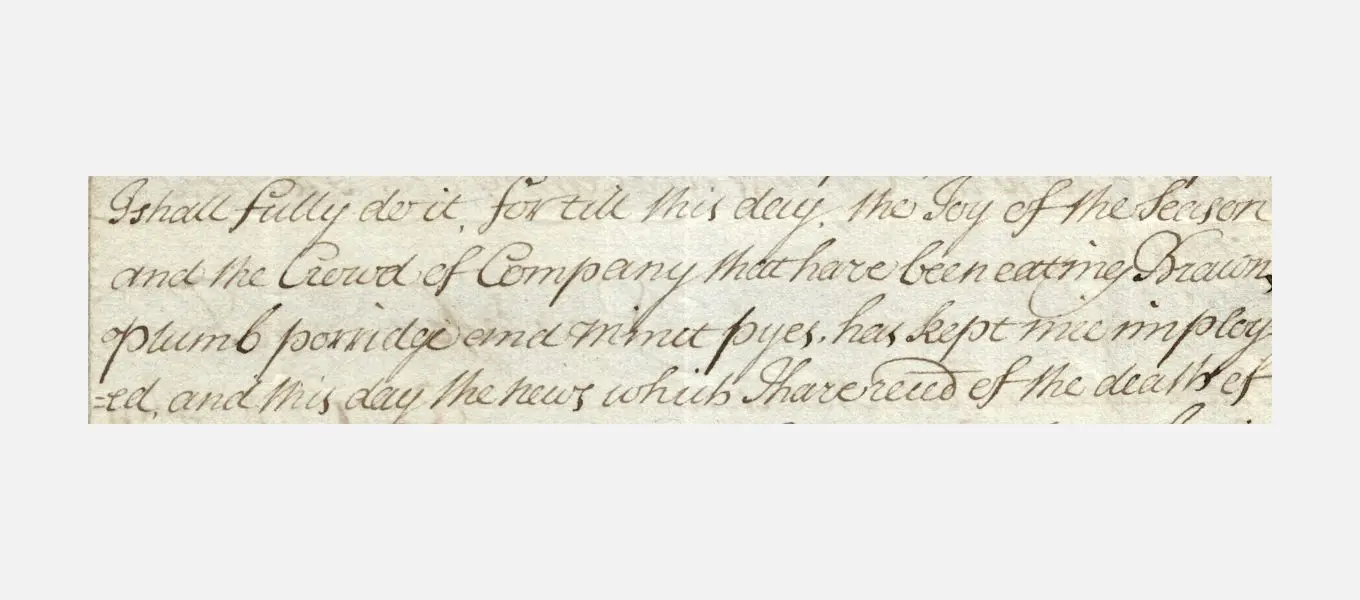

In this extract from a letter written by the 1st Earl of Burlington on 30 December 1696 (below), he explains that he will not be able to answer all the letters he is due to write until Christmas festivities are over, ‘for till this day, the Joy of the Season and the Crowd of Company that have been eating Brawn, plumb porridge, and minct pyes, has kept mee imployed’.

Brawn was a popular traditional Christmas food: it was a moulded jelly made from the boiled head of a calf seasoned with spices. Plum porridge was an old English dish which mixed sweet and savoury flavours: broth made from boiled beef and thickened with bread was mixed with spices, dried fruit, sugar and wine. Similarly, mince pies were filled with real meat, often leg of mutton or another cheap cut. This was complemented by spices like cloves and mace, with dried fruit and some alcohol, encased in a hot water crust pastry.

Family traditions

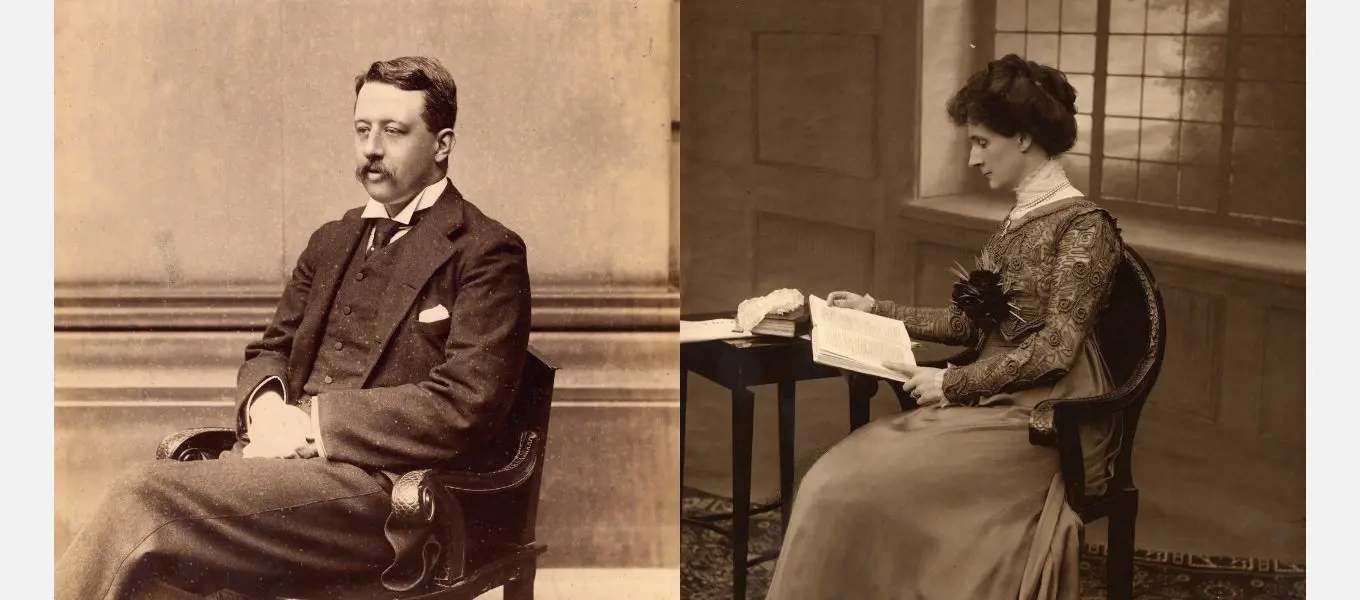

Moving forward in time, the best insight into late 19th and early 20th-century Christmas is offered by the extensive papers of Victor Cavendish, who became 9th Duke of Devonshire in 1908, and his wife Evelyn.

The earliest examples of Christmas cards in the archives are found amongst the 9th Duke and Duchess's papers.

The origin of the Christmas card is dated to 1843 and attributed to civil servant and inventor Sir Henry Cole, who commissioned a standard card to send to friends when he found he did not have time to respond personally to every Christmas letter he received. Sending cards only became really widespread in the 1860s, but before the 1890s cards do not generally appear to have been preserved by Cavendish family members.

Shown above are some examples from 1902. They provide a snapshot into the tradition at the turn of the 20th century, and include some familiar motifs as well as others which are less familiar – the frequent use of the term ‘hearty’, the emphasis on ‘remembrance’ of friends and acquaintances, and a certain Scottish influence, with thistles and terms like ‘auld lang syne’, which we now associate with New Year rather than Christmas.

The 19th century also saw present-giving shift from New Year to Christmas Day, and Lady Evelyn put much time and thought into buying Christmas presents – often taking advantage of her husband Victor’s visits to London as an MP to provide him with lists of presents to purchase from London stores. Her letters also give us an insight into the kind of items that were being exchanged as gifts at that time.

In this letter of 29 November 1894, Lady Evelyn writes to her husband who is in London:

‘You good old thing to bustle out and do shopping! I find your mother would like a travelling clock. There are nice ones in leather cases, not very dear, so if the kettle is too big a present you might get that instead, and let the boys give her a copper one on a stand. Or we could give her a good electro plated one. Only that does not sound so nice as silver. I am sure she would like a kettle very much.’

While in the 17th century, the family tended to spend Christmas at Hardwick, their main Derbyshire residence at the time, or in London, the 9th Duke and Duchess Evelyn focused their Christmas celebrations on Chatsworth.

They had seven children and many more grandchildren, who in the 1920s and 30s would descend on Chatsworth for the festive season with all their travelling servants – meaning there could be up to 150 people in the house for Christmas.

Images: 1. Victor Cavendish, 9th Duke, with 17 of his grandchildren taken in the garden at Chatsworth, Christmas 1930, (for a 'who is who' please see below), 2. the 9th Duke's grandchildren in the garden in 1929, 3. 9th Duke and Duchess Evelyn with grandchildren, taken at Christmas 1934

On Christmas Day there were two trips to church and some opening of presents in the morning; after luncheon there would be some form of outdoor exercise followed by afternoon tea with Christmas cake.

The Christmas tree would then be lit in the Painted Hall, and the Duke and Duchess would give out their presents, which included gifts for the entire household and all the visiting servants.

Image: Christmas at Chatsworth 1926, the 9th Duke and Duchess Evelyn with their children and grandchildren, and Lord and Lady Lansdowne. For a 'who is who', see below.

Food was an important part of Christmas Day. There would be a large luncheon and a similarly substantial dinner served in the Great Dining Room in the evening. A few menus survive in the archives; shown here are two Christmas Day menus – one for luncheon and one for dinner.

Christmas food had moved on since the 17th century: while there are some traditional English dishes like plum pudding and mince pies, there is also an obvious French influence. Many of the dishes consumed were recipes by, or inspired by, the great French chef Auguste Escoffier, who worked at the Savoy Hotel in London in the 1890s, and the Carlton from 1898-1921, and had a strong influence on the food eaten by high society.

The main course for both luncheon and dinner shown here is turkey – roasted with vegetables for luncheon, and served with chestnuts as well as vegetables for dinner (a traditional French Christmas dish). The starter for luncheon – gnocchi au gratin – is an Escoffier recipe. There are no potatoes involved here: it is a classic gnocchi made of milk, butter, flour, eggs, salt and nutmeg which is poached and then baked with a cheese sauce. Cold meats and salad followed the turkey, and for dessert there was plum pudding or mince pies (or perhaps both for those who had room).

A significant amount of afternoon exercise would have been needed to work up enough appetite for dinner, bearing in mind that Christmas cake was also consumed during the afternoon. For a wealthy family, the starter of turtle soup would have meant actual turtle meat, whereas ‘mock turtle’ (made from calf’s head) was more usual at this time.

The fish dish – ‘filet de sole dejazet’ – is an Escoffier dish in which the sole is covered with tarragon butter and served with poached mussels and shrimps’ tails, covered in a white wine sauce.

For those unable to face another helping of plum pudding, a slightly lighter alternative is provided in the form of ‘omelette surprise’ – a baked alaska.

Although customs and tastes have changed over the years, the archives reveal how the festive season has always been a time for people to come together and celebrate, to exchange gifts, and to share written news and greetings with a wider network of family and friends.

Main banner image, above - the 1932 family Christmas card showing the 9th Duke and Duchess of Devonshire posing with their grandchildren.

9th Duke and his grandchildren: (from left to right), Peter Baillie, 9th Duke of Devonshire holding Sarah MacMillan, Anne Cavendish, John Cobbold, Elizabeth Cavendish, Catherine Macmillan, Judith Baillie, John Stuart, Michael Baillie, David Stuart, Carol Macmillan, Jean and Pamela Cobbold, Maurice Macmillan, Andrew Cavendish (later the 11th Duke of Devonshire), Arbell Mackintosh and William Cavendish.

Christmas at Chatsworth 1926: (back row, left to right) Lord Charles Cavendish (1905-1944), who married Adele Astaire and resided at Lismore Castle in County Waterford, Ireland. Lady Dorothy (1900-1966), who married former British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan. William 'Billy' Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington (1917-1944), he was the eldest son of the 10th Duke and was killed in action just four months after marrying Kathleen Kennedy, sister of US President J.F Kennedy. Lord Andrew Cavendish, later 11th Duke of Devonshire (1920-2004), 9th Duke, (centre front row, left to right adults) Lady Lansdowne, Lord Lansdowne (Duchess Evelyn's parents) and Duchess Evelyn.